I’m not a fan of calling out people for different opinions. After all, many things work in fitness and nutrition, and endless concepts and theories are still being explored. So, for personal health, on some level, if it works for your health, then it works for you.

But, sharing personal experience and recommendations is much different than posing opinions or beliefs as if they are undeniable scientific facts. You have to draw the line at manipulating research or just straight-up lying because your health is too important.

That’s what happened when Tracy Anderson twisted the benefits (and dangers) of strength training, and it’s happening more and more at a frightening pace. Too many “experts” just make up information, present them as facts, and the result is you are more confused than ever. It’s not OK, so let’s cleanse you of the ridiculousness and offer a taste of reality.

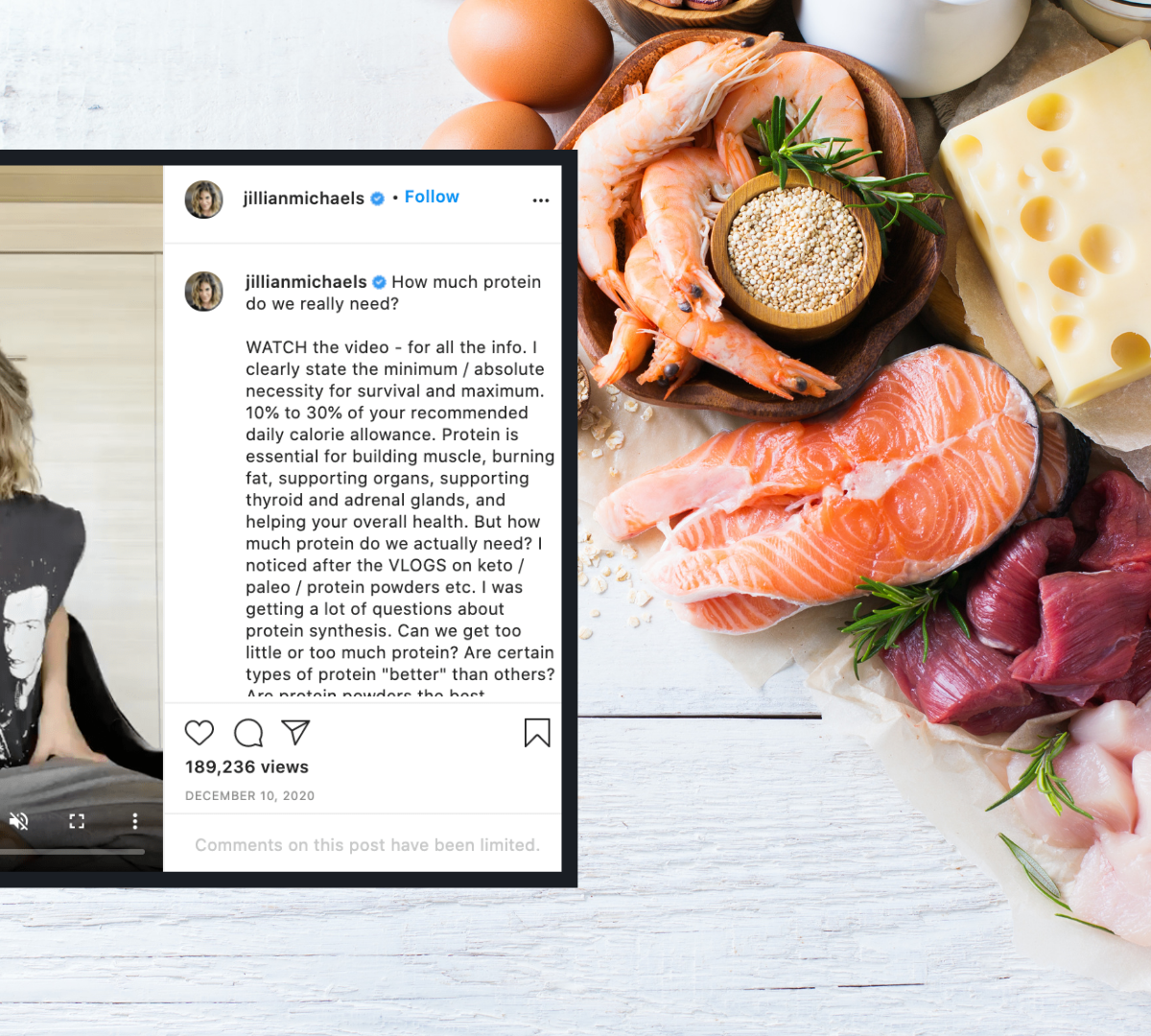

In a recent Instagram post, Jillian Michaels (of The Biggest Loser fame) shared the “dangers” of eating more than 30% of your daily calories from protein. “Dangers” are in quotes for a good reason.

She claims a higher-protein diet will cause the following: bone loss, kidney stones, liver stress, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, heart disease, and early aging.

Her scientific proof for these claims? As she stated in the video, “Trust me, I could give you a bunch of different studies, it would take all day. You don’t want more than 30 percent protein. It’s not a good thing.”

Well, then. Unfortunately, she made very definitive claims, many of which are simply not supported by science.

When questioned on her IG posts, she followed up by saying something along the lines of, “But, Dr. Sinclair says this!” (Dr. Sinclair is a Harvard researcher who studies aging).

With millions of followers, this is the equivalent of nutritional negligence. Your followers likely haven’t read Dr. Sinclair’s work. And, many of his claims were not mirrored by you with the nuance and detail needed. If you’re going to share other’s work, you can’t cherry-pick data.

Respected researcher Dr. Brad Schoenfeld might have put it best in his response to the post, “Pretty much every sentence is an over-extrapolation of evidence or an outright falsehood.”

The problem isn’t the advice (“Eat 30 percent protein or less.”) — it’s the rationale and manipulation of evidence (“Protein kills your kidneys!”), which is designed to create fear, rather than educate.

You know the quote, “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.”

What happens if you make people fear eating too much fish?

As you’ll learn in a moment, it can be a big problem, which is why something had to be said.

Jillian makes absolute claims about what happens when you eat higher levels of protein that aren’t accurate. Eating too much protein might potentially have some downsides. But, if you’re going to help people out, you need to include the essential details.

It’s a lot to untangle, but here’s what you need to know, which details were extremely misguided, and where you might need to think twice about your protein consumption.

Fact: Protein Is Essential

Let’s not get it twisted: Your body needs protein. End of story. Jillian was right on this. She said it’s a need, and it is. Protein is the building block of all the cells in your body. From building muscle and helping with cellular processes to improving your hair, skin, and nails, it’s an incredibly valuable nutrient.

Fiction: There’s Reason to Fear Protein

I covered the origins (and flaws) of protein fear back in this blog post from 2015.

In the past, crazy headlines have included “High protein is as bad as smoking.” It caused me to write a rebuttal about how protein is not a death sentence. After all, if you’re going to critique protein, you need to accept all of its general health benefits:

“The adverse potential of not getting enough protein (sarcopenia, compromised glucose control, lower immunity, brittle bones), especially in the aging population, far outweighs the risks of getting too much.“

Your body is complex. Creating fear around a singular macronutrient causes dominos to fall into multiple directions, and they might not all be in your best interest.

You need to consider 3 basic factors:

1. What proteins are you eating?

It’s one thing to reduce the total amount of protein. But, what proteins were you eating in the first place? Processed meats or wild fish?

2. If you decide to eat less protein, what are you replacing it with?

Similarly, if you reduce protein — what are you replacing it with? If you’re going to strike fear in protein, it’s best to give direction about alternatives.

3. Are you even eating too much protein in the first place?

And, maybe most importantly, the majority of people are nowhere close to eating more than 30% of their calories from protein. According to Harvard, about 16 percent of the average American diet comes from protein.

Most people also don’t count calories. So, on a practical level, if you hear, “Don’t eat protein,” the natural reaction is to eat less, even if the amount you’re consuming doesn’t present any danger.

It’s why presenting protein as dangerous, especially without details, can cause trouble.

Speaking on dangers…

Fiction: High-Protein Diets Harm Healthy Kidneys (They DON’T)

Jillian claims higher protein leads to kidney problems and early death. This is an outright false statement, and the research is (to this point) very definitive on the matter.

This meta-analysis from 2018 found that higher-protein diets do not harm healthy kidneys. This has been proven over…and over…and over…and over again.

If you have kidney disease, then you should consult with your doctor. Otherwise, there’s no reason to fear.

Fiction: Protein Causes Bone Loss. (It doesn’t, but there’s something you need to know)

What about Jillian’s claims about protein and bone loss? We know that calcium is important to bone health. And, as it turns out, so is protein. In fact, there was a study from 2019 titled, “Optimizing Dietary Protein for Lifelong Bone Health.” Here’s a takeaway you might find interesting:

In addition to calcium in the presence of adequate vitamin D, dietary protein is a key nutrient for bone health across the lifespan and therefore has a function in the prevention of osteoporosis. Protein makes up roughly 50% of the volume of bone and about one-third of its mass. The bone protein matrix undergoes continuous turnover and remodeling; therefore, an adequate supply of amino acid and mineral substrate is needed to support the formation and maintenance of bone across the lifespan.

OK, so we know protein is important, but what about too much protein? It’s true that protein can increase protein excretion — but it doesn’t lead to bone loss. This is because protein also increases calcium absorption.

Some might point to the acidity of meats breaking down your bones…but that’s also been shown to be inaccurate.

For the majority of people eating typical western diets with acid loads of ≤1 mmol/kg, whose renal function and acid-excretory ability are normal, dietary acid loads would not be a readily detectable factor in altering bone mineral density leading to the development of osteoporosis. Other factors such as age, gender, race, and immobility are quantitatively more major factors in determining bone mass and bone breakdown.

To this point, there isn’t strong support that high protein diets lead to bone loss, and the lack of connection is backed up by leading organizations that focus on your bones.

The IOF and European Society for Clinical and Economical Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases now advise that dietary protein levels above the current RDA in the United States and Canada, regardless of the source, may be beneficial in reducing bone loss and hip fracture risk, provided calcium intakes are adequate.

The key to bone health isn’t how much protein you eat, but — rather — making sure you have enough calcium.

The Latest on Protein and Cancer (Connection But Not Clear Causation)

Next up: cancer. I don’t mess with cancer. My father is battling stage 4 right now, my older brother has battled cancer twice, pancreatic cancer took my grandfather. To put it simply: cancer has ravaged both sides of my family, so risk factors and causes are of personal interest.

The relationship between protein and cancer seems to be — on some level — linked to the type of cancer. With regards to pancreatic cancer, research suggests that higher-protein diets don’t lead to greater risk. The same can be said about higher protein and colorectal cancer.

With breast cancer, research suggests that certain foods might increase risk, depending on how much you eat and source. From a 2017 meta-analysis:

There was a null association between poultry, fish, egg, nuts, total milk, and whole milk intake and breast cancer risk. Higher total red meat, fresh red meat, and processed meat intake may be risk factors for breast cancer, whereas higher soy food and skim milk intake may reduce the risk of breast cancer.

Again, the question here is about the quantity of protein intake. And, the conclusive evidence that eating more than 30 percent of your diet causes cancer just doesn’t exist.

In fact, a 2020 meta-analysis of more than 30 studies looked at the relationship between total protein, animal protein, plant protein, and cancer. Their conclusion:

Higher intake of total protein was associated with a lower risk of all cause mortality, and intake of plant protein was associated with a lower risk of all cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Replacement of foods high in animal protein with plant protein sources could be associated with longevity.

Now, some research — mostly in rodents — has assessed the impact of certain amino acids (such as BCAAs and methionine) and the impact on a variety of biological factors that might influence aging (and as a byproduct) cancer. These include things like mTORC1, Mnmt, SAM metabolism, fibroblast growth factors, and oxidative stress and inflammation.

These are all fascinating areas of research for anti-aging and cancer, but the research is fairly early (and mostly in animal models) to be able to make any conclusive claims on the risk of total protein, irrespective of lifestyle behaviors and dietary choices. As time goes on, we should certainly learn much more about what is a real risk factor (and what’s not).

(Note: If you have cancer, many doctors might suggest that you adjust your diet and protein intake. What causes cancer and how you fight cancer are two different considerations and shouldn’t be confused.)

The Complicated Relationship Between Protein and Heart Disease

Finally, Michaels claims a strong link between more protein and heart disease. This one is tough because if you’re measuring heart disease, you need to control for lifestyle factors and can’t just look at protein in a vacuum. That’s because we know lifestyle factors — such as smoking, high blood pressure, stress, bodyweight, etc. — all are the main triggers for heart issues.

That’s not to say protein is completely off the hook. There is some research that certain foods might create a “marginal increase in risk” for heart issues, dependent on the source of protein and a variety of other factors. But, the research is mixed.

If you control for lifestyle factors (like smoking), as they did in this study of 80,000 women over 25 years, they found that protein intake had an inverse relationship with heart disease. From their conclusion: our findings suggest that replacing carbohydrates with protein may be associated with a lower risk of ischemic heart disease.

Much like cancer, the research isn’t conclusive on the impact of total protein, although protein source and calories could have an impact. To quote Dr. Schoenfeld:

“The researchers are lumping ‘animal protein’ into an entire group, but it very well could be other aspects of the diet that are having the impact other than protein. Were the meats processed? If so, could be something in the processing. How were the meats cooked? Could be due to carcinogens from overcooking the meats. What was the fat content and breakdown of the fat profiles (i.e. saturated, MUFA, PUFA)? This could be an issue. What about total caloric intake? There are so many potential confounding issues that it makes drawing any conclusions extremely difficult. Simply looking at data from observations can be very misleading.”

Your Takeaways: How to Eat Protein and Be Healthy

What should you make of it all? For starters, Jillian Michaels needs to pump the breaks on absolute statements that are absolutely not conclusive, and — in some cases — completely false.

There are many things she could have said that wouldn’t raise any red flags, such as recommending no more than 30% protein because she feels that’s enough for most people’s goals and needs. That would be solid advice and harmless. Instead, she tried to rationalize her own beliefs with lies and twisted science that does a lot of damage and creates a tremendous amount of confusion.

If you can avoid the absolute fear, the debate about protein can provide you with some valuable guidelines for your own life. Within the last 5 years, my own approach to protein has shifted based on research and my conversations with my doctors.

Here are a few aspects that can help you determine how to fit protein into your diet:

- The fear of higher-protein diets is significantly overblown. Protein is important and has many benefits that extend from how you look (fat loss and muscle gain) to how well you age. For metabolic factors and satiety, it’s helpful to include, at least, some protein in meals and snacks.

- In general, a moderate-to-high protein diet is good for body composition, and lower body fat.

- The protein source is a big consideration. There’s a big difference between eating wild-caught salmon and processed or over-cooked meats.

- When adding protein to your diet, if you want to follow the current science, prioritize the following: fish, eggs, dairy (including whey or casein protein powders), nuts, legumes, and poultry. They tend to — for the most part — not be seen as risk factors for disease.

- Red meat is not off-limits, but the most “heart-healthy” diet (the Mediterranean Diet) limits overall red meat. A general rule of thumb is eating red meat 1-2 times per week or several times per month. [Note: some people handle red meat great and others don’t. If you really want to dig in, get blood work done and discuss with your doctor.]

- If you have concerns, see your doctor, get blood panels, and assess what’s happening inside your own body. This will be the best indicator of any potential risks and adjustments you need to make.

Adam Bornstein is a New York Times bestselling author and the author of You Can’t Screw This Up. He is the founder of Born Fitness, and the co-founder of Arnold’s Pump Club (with Arnold Schwarzenegger) and Pen Name Consulting. An award-winning writer and editor, Bornstein was previously the Chief Nutrition Officer for Ladder, the Fitness and Nutrition editor for Men’s Health, Editorial Director at LIVESTRONG.com, and a columnist for SHAPE, Men’s Fitness, and Muscle & Fitness. He’s also a nutrition and fitness advisor for LeBron James, Cindy Crawford, Lindsey Vonn, and Arnold Schwarzenegger. According to The Huffington Post, Bornstein is “one of the most inspiring sources in all of health and fitness.” His work has been featured in dozens of publications, including The New York Times, Fast Company, ESPN, and GQ, and he’s appeared on Good Morning America, The Today Show, and E! News.