Talking about squats is a lot like talking about politics: Everyone has an opinion on what works and what doesn’t—and, chances are, they’re passionate about it.

But, it doesn’t take long to realize that the squatting commandments you’ve been hearing for years are very flawed. Case in point: ever been told that your “knees shouldn’t go over your toes” during the squat? Somehow, this idea has lived for decades despite the fact that it’s not true.

Automatically assuming that your knees shouldn’t go over your toes is a great way to ensure that you put a lot of stress on other structures, such as your lower back (as a result of hips), hamstrings, or even your calves. If you’ve tried this approach, you might find that squatting suddenly feels very uncomfortable (note: uncomfortable is different from difficult). And, that’s never a good thing and likely a sign that the movement you’re forcing isn’t going to make your body feel good.

Research supports why allowing your knees to go over your toes isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In one study, participants were restricted from moving their knees in front of their toes. The results? It led to a slight reduction in knee torque (22%) but at the cost of a massive increase in hip torque (1070%).

This suggests that if you apply a movement standard for everyone, it’s likely to cause stress in unintended ways, and this massive increase in stress is likely to lead to injuries, aches, and pains.

It’s perfectly fine for your knees to go over your toes as long as your heels are planted on the ground and your weight is balanced over your natural center of gravity.

The only squat stance that is “right” is the one that is suited for your body. That means it’s time to unlearn what you’ve been taught and start figuring out a better way to squat for your body. Once you do, everything feels better, hurts less, and you’ll become stronger.

Is Squatting Good For You?

“Is it good to squat?” is a fair question, but one with an easy answer. Yes. Sitting down and standing up is one of the most basic movements in life.

Whether squatting is good is not a debate, but form and depth are topics of intense disagreement. The biggest thing you need to remember is that everyone is going to squat a little differently. Your squat form might not look like the ones you see in the pictures or those little “squat form demonstration” illustrations.

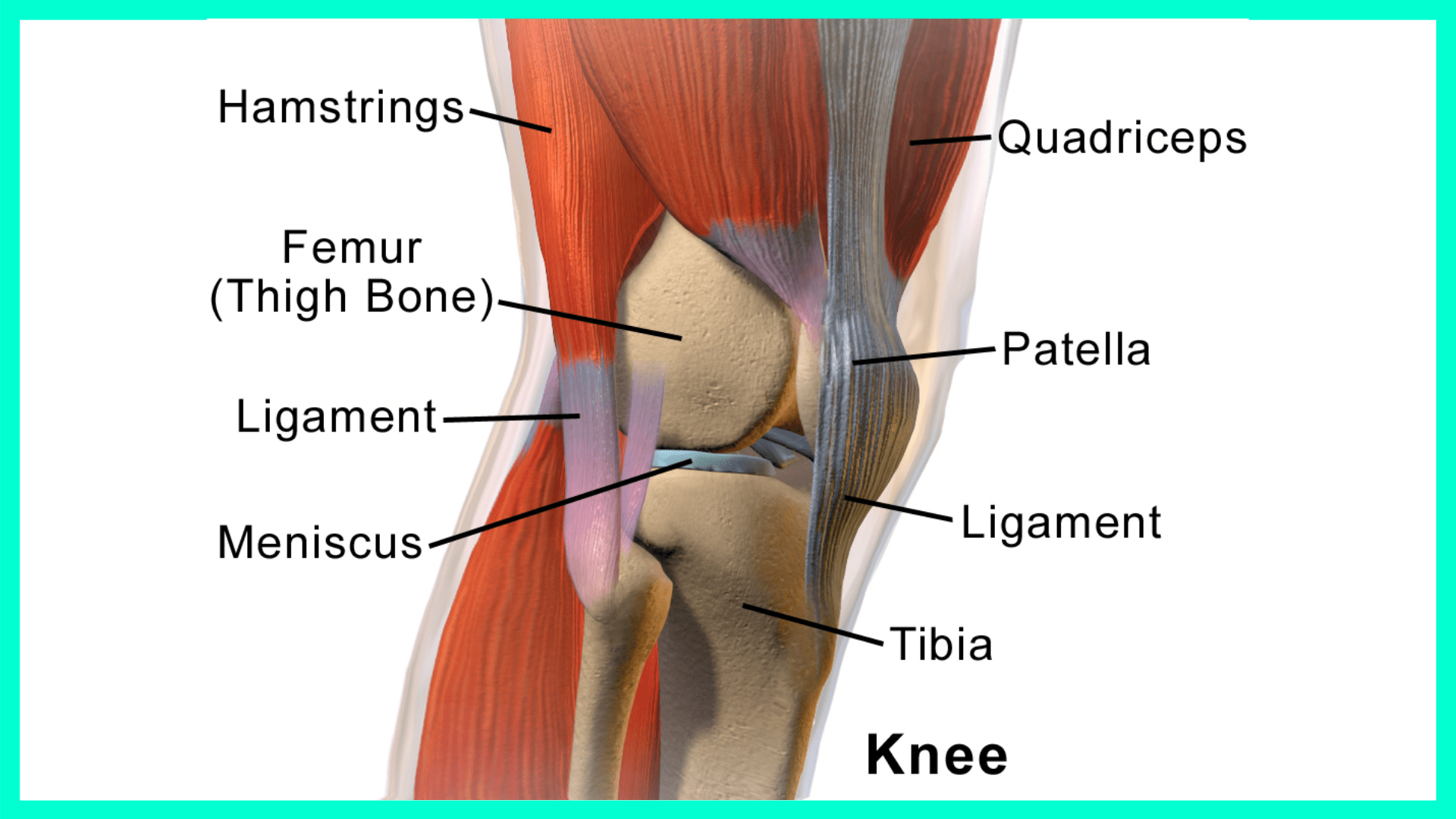

Your knee attaches to 3 main muscle groups: your hamstrings and calves in the back the quadriceps in front. These muscles also play a key role in your hip movement. Translation: When your muscles contract, they work together to balance out force and keep your knees (and other structures) healthy.

Remember the study we mentioned above and how it increased hip torque by more than 1,000 percent? Trying to follow those how-tos might be why your squat form doesn’t feel quite right—or perhaps why squats feel painful. Following a movement built for someone else’s body type isn’t a good idea.

This, of course, is the reason why squats hurt so many people, get a bad reputation, and why you are often tempted to skip this move in your workout, even though you should do it.

No one is going to give you an extra million dollars for squatting deeper.

Making matters worse, the more that you read about squat form, the more likely you are to find conflicting information. On one side you have the purists. They’ll tell you that you must squat “ass-to-grass.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum, are the overly cautious types who worry that squatting too low will damage your knees (it won’t, by the way). And there are plenty of others who will advocate for stopping at seemingly every other point in between—thighs parallel to the ground, or just below it, or well above it (known as quarter squats), and on and on.

No one is “right” but everyone is wrong unless they are showing you how to figure out the right squat depth and stance for your body.

“There’s no one right way to squat—and there’s no one wrong way, either,” says Dean Somerset, C.S.C.S., an exercise physiologist in Edmonton, Alberta Canada. “It’s all about finding what works for your body.”

What’s right for you depends on your goals, strength, and level of mobility, which are things you can influence. But, not everything that determines how well you squat is within your control.

Your body’s bone structure will affect how you move too. Because of all that, many of the standard squat cues you hear about where your feet should be or what direction they should point may not actually work for you. (But don’t worry, we’ll show you what will.)

The bottom line: Forget the politics. Forget all the “one-size-fits-all” opinions. There are a lot of ways you can go about fixing squats when they hurt. We’re going to break down the different types of squat depth and share a test that can help you start to personalize your approach.

By the time you’re done reading, you’ll know the right range of motion for your body, so you can get the most out of the squat.

The Deep Squat

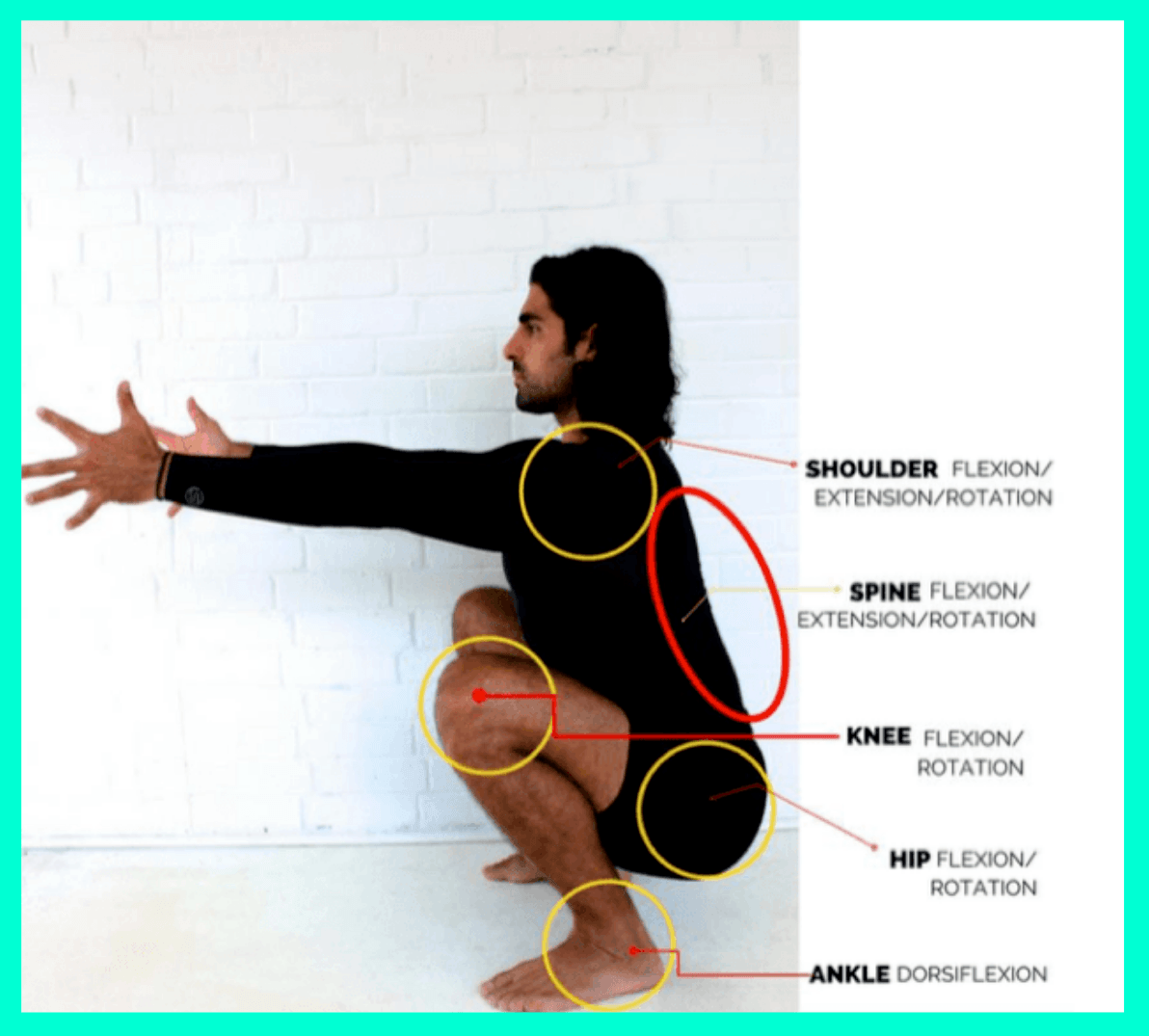

Being able to execute a full deep squat is a good thing, but it might not be your thing. Doing the move requires a full range of motion at all four of the body’s major load-bearing joints (the ankles, knees, hips, and shoulders) and proper mobility throughout the spine. Those joints, your muscles, and your brain all have to work together to achieve this position:

That demonstration comes from Georges Dagher, C.S.C.S, a chiropractor and strength coach based in Toronto. He likens the deep squat to brushing your teeth. “From my perspective, the deep squat movement is a toothbrush for our joints, ensuring they are all moving without any sticky or restricted areas,” Dagher writes in the Journal of Evolution and Health.

Just as you brush your teeth every day, Dagher suggests performing at least one bodyweight squat per day, as deep as you can.

If you look at the photo above and think “no way,” don’t stress. Lots of people have strength or mobility issues that can make achieving a deep squat challenging—at least at first.

The good news? By simply working on your deep bodyweight squat form, going as deep as you can with control, and holding as long as you feel reasonably comfortable, you’ll help address and improve those issues.

“The positions we place our bodies in will have an effect on various elements such as muscles, which can improve our comfort in the squat,” Dagher says.

You can also get more comfortable by adjusting your stance. Somerset explains that the standard squatting position— “stand with your feet shoulder-width apart…” —doesn’t apply to everyone. It’s more of a general recommendation or an average, he says, not a hard-and-fast rule.

To help his clients reach a deeper, pain-free squat, Somerset has them experiment with different stances until they find one that feels right.

“Think of it like going to the optometrist, when they put the lens in front of your eyes and ask which one is better,” Somerset says. “There’s no one standard prescription. It’s about finding the right one for you.”

Here are the two main elements Somerset asks clients to adjust when they dial in their stances for ideal squat form:

- The direction of your toes: Try them pointing straight ahead first. Let’s call that 12 o’clock. Squat as deep as you can. Now turn your feet outward slightly – think left foot pointing at 11 o’clock, right foot pointing at 1. Try the deep squat again. Now angle them even farther outward, to 10 and 2. Squat again. Notice which position feels the most natural and allows you to sink the deepest.

- The width of your feet: Start with them set shoulder-width apart. Then, gradually try wider distances, giving each the bodyweight squat test and noticing which feels the most natural. One thing to note: The wider your stance is, the more the exercise will emphasize your glutes (the muscles in your butt), and the less work it’ll put on the quads (muscles of your upper leg around the knee).

Here’s more good news: Even if your range of motion is limited, you probably squat more throughout the day than you think. “Most of us can squat to at least a 90-degree angle,” says Dagher. “We do that every day, every time we climb into our car or get up from a chair.”

Each of those moments is an opportunity to practice lowering yourself into a 90-degree squat with control. Think of them as box squats you do throughout the day; don’t just plop onto the cushion, says Dagher. Doing this throughout the day can shore up your stability and make you a better squatter in the future.

Why You Can’t Squat Deep

Bodyweight squats are one thing, says Dagher, who says that, with the right adjustments, pretty much everyone can go into a deep squat. But, Somerset points out that weighted squats are a different story.

“For some people, their squats fall apart under a certain amount of loading,” he says.

You see, even if you’ve maxed out your mobility in your joints, when it comes to doing weighted squats, you may not be as comfortable—or as powerful—at the deeper end of the squat as you’d like, says Dagher.

Why? It comes down to simple genetics. Some people are built with better squatting hips than others.

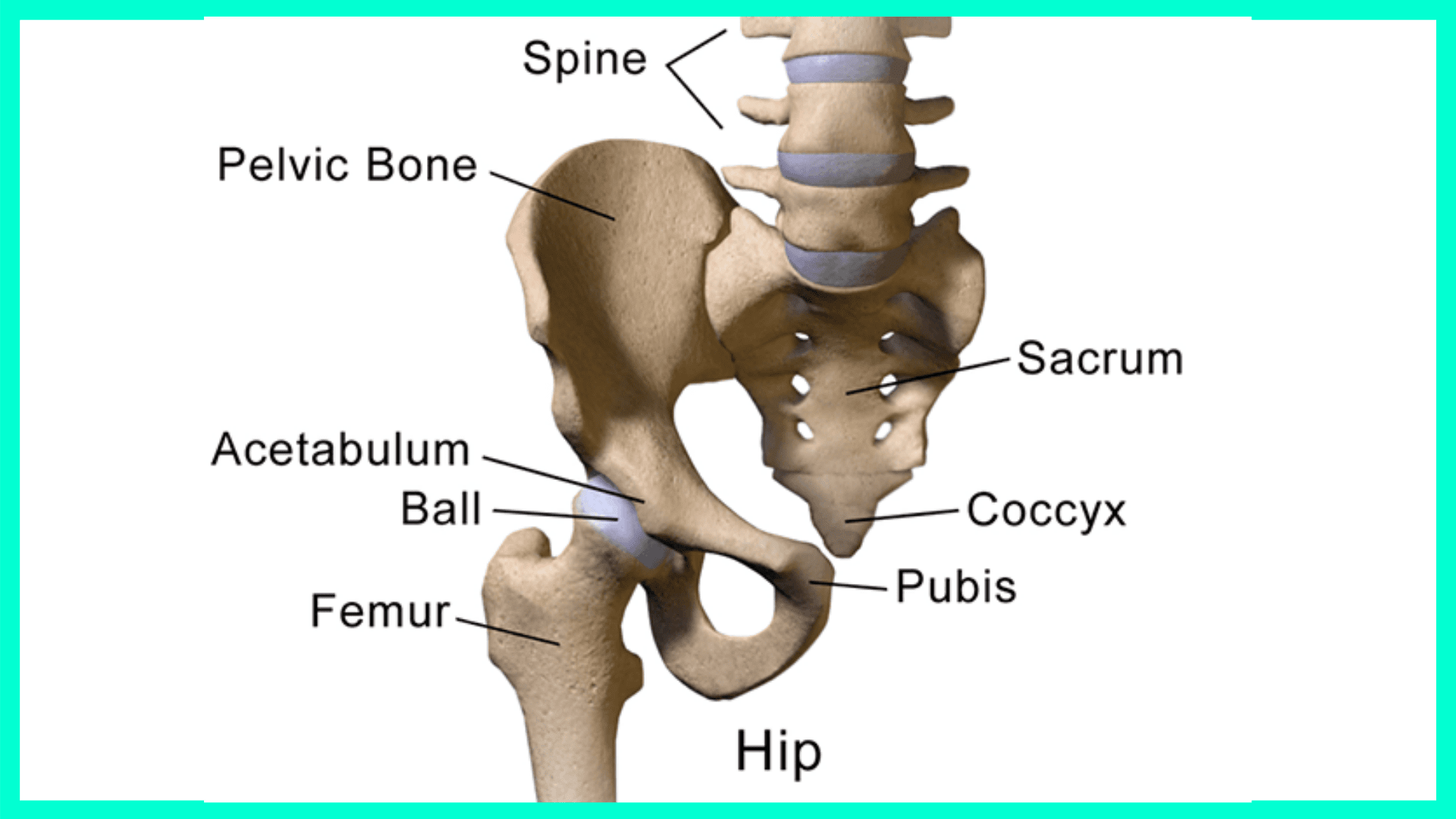

Quick anatomy lesson: The place where the femur (the big bone in your thigh) meets your hip, called the hip socket, looks something like a spoon going into a bowl. The top of the femur (called the femoral head) neatly fits into the pelvic socket (acetabulum) and is held in place by ligaments.

Everyone’s hip sockets are different. Some of them are deeper than others. The deeper your socket, the harder it will be for you to squat, since the femur bone will hit the pelvic bone. To go back to our “spoon in bowl” analogy, the stem of the spoon (your femur) runs into the rim of the bowl (your pelvis).

People of Scottish and French heritage typically have deeper hips, according to world-renowned spine expert Stuart McGill. Meanwhile, people from the Ukraine, Poland, and Bulgaria tend to have shallower sockets that allow them to painlessly sink into the deep part of the squat.

McGill says it’s no coincidence that Eastern Europe is home to some of the best Olympic lifters in the world.

A deep hip socket has different advantages. It’s helpful for walking and standing and great at producing rotational power (the type of force you need to hit a baseball or swing a golf club). And having deeper hip sockets doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t squat deep. But, it does mean you’ll have to work harder on the move—and may feel pain when you perform it.

The Squat Form Test

There’s a simple way to gauge the depth of your hip sockets. Simply get onto your hands and knees in an all-fours position, engage your core, and slowly rock your hips back toward your heels. You can see Dr. McGill explain how to do the move at the 2:50 mark of this video (although the entire clip is worth a watch if you have the time).

While it’d be great if you too could do the move under the guidance of the world’s leading researcher on spinal health and performance, you can do this assessment on your own. Simply set up your smartphone to your side, hit record, and do the move.

As your hips lower, you may reach a point where your lower back starts to round. The technical term for that is “spinal flexion.” When it happens while you’re squatting with a barbell on your back, the position is known by the delightful name “buttwink.”

Fun as that word may be to say out loud, buttwink while squatting under load can be bad news. “That’s when your hips stop moving and your start compensating with your back instead,” says Dagher. Disc injuries or even fractures of the spine can result.

How Deep Should You Squat?

The buttwink is why you should not view the weighted deep squat as something you must perform.

As McGill says, a lot of great ATG squatters “chose their parents wisely.”

“The extreme amount that I see people deep squatting is just unprecedented,” McGill says. “The risk is greater than is justified by the reward. No one is going to give you an extra million dollars for squatting deeper. If you need to do that for competition, then that’s one thing. But if your objective is health, then it’s pretty hard to justify.”

The same isn’t true for deep bodyweight squats, however. “Buttwink here is not an issue,” Dagher says. Go ahead and wink away when you’re working the deep squat without weight with the goal of improving your mobility and comfort in the squat.

But, where your back begins to go into flexion when you’re doing the all-fours test, that’s where you’d want your descent to stop if you were performing weighted back squat. If that means you can only squat as low as a box, no problem.

If the box isn’t high enough, you can take a cue from Jim Smith, C.P.P.S, and stack mats on top of the box until you reach the right height. As your mobility and ability to squat lower improve over time, you can pull mats off the pile. No matter what height you reach, Somerset says your main objective should be one thing: control.

A deep range of motion isn’t meant for everyone, so don’t overthink your squat form. In fact, for many people, trying to reach more depth can be counterproductive–or even dangerous. And for no reason.

Less depth doesn’t mean less strength or muscle. But, it also doesn’t mean creating such a short range of motion (like moving 2 inches, so it looks like you’re bouncing up and down) that you’re not creating tension in the muscles, challenging your body, or doing the exercise in a controlled manner. That’s just called cheating.

“Keeping the squat controlled is more important than the depth or the amount of weight being used,” says Somerset.

Hit the height that’s right for you, with the stance that’s right for you, using a weight that you can manage. And then work the deep bodyweight squat. You’ll soon find that you’ll improve your squat form, will move better, and you will become a lot stronger, too.

READ MORE:

Why Do Squats Hurt? (And How to Fix the Problems)

6 Exercise Upgrades for Better Results

The Tension Weightlifting Technique: How to Make Every Exercise More Effective

Adam Bornstein is a New York Times bestselling author and the author of You Can’t Screw This Up. He is the founder of Born Fitness, and the co-founder of Arnold’s Pump Club (with Arnold Schwarzenegger) and Pen Name Consulting. An award-winning writer and editor, Bornstein was previously the Chief Nutrition Officer for Ladder, the Fitness and Nutrition editor for Men’s Health, Editorial Director at LIVESTRONG.com, and a columnist for SHAPE, Men’s Fitness, and Muscle & Fitness. He’s also a nutrition and fitness advisor for LeBron James, Cindy Crawford, Lindsey Vonn, and Arnold Schwarzenegger. According to The Huffington Post, Bornstein is “one of the most inspiring sources in all of health and fitness.” His work has been featured in dozens of publications, including The New York Times, Fast Company, ESPN, and GQ, and he’s appeared on Good Morning America, The Today Show, and E! News.

Good article. I realized I was going to low in front squats. My form down low was bad, and my lower back was having to over work because I would lean forward to much. I modified my form and stopped just before my form would break. Still it is pretty low, but doing this better worked my muscles and different cause lower back strain.